I think my title is a pun in Greek! Hemiola and hemophilia both come from ancient Greek, but from different words. Hemiola comes from ἡμιόλιος meaning "one and a half" and it refers to the practice of putting three beats where there would normally be two. Hemophilia comes from the Greek haima αἷμα 'blood' and philia φιλία 'love' and refers to a medical condition where the blood does not clot properly.

So someone who was in love with hemiola would be a "hemiolaphiliac". Or something.

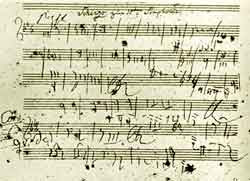

Hermiola is a very interesting rhythmic effect that comes from changing the grouping of beats. We first start seeing it in Spanish music in the 16th century. It usually occurs in triple time as follows. This is from a Baxa de contrapunto by Luys de Narvaez published in 1538:

The hemiola occurs in the third and fourth measures when tieing the A over the barline turns two measures of 3/4 into one measure of 3/2. This became a popular way of signalling a cadence in the Baroque. But the hemiola became quite ubiquitous in Spanish music. A famous example is this Canarios by Gaspar Sanz from the 17th century:

Instead of just appearing at the end or a cadence, this alternation between two groups of three beats and three groups of two beats, shown in the example by the changing time signature from 6/8 to 3/4, happens throughout the piece. We find this a typical rhythmic effect in Spanish music. It appears at the beginning of the famous Concierto de Aranjuez for guitar and orchestra by Joaquin Rodrigo:

There are a couple of nice things about this deceptively simple opening. First of all, it is a three-measure phrase, which is unusual. It has an urgency about it that comes from squeezing the last two measures of a theoretical four-measure phrase into one. The first two measures are a typical hemiola. The third measure is a compressed version of the same hemiola! Let's listen to that opening:

Very nice. Do you hear how that third measure throws us forward? The unusual rhythmic patterns of flamenco underlie a lot of Spanish music. The history of flamenco is somewhat obscure, but undoubtedly some of its unusual handling of rhythm and timbre, by European standards, comes from the long occupation of Spain--some 700 years--by the Moors. One hemiola-related pattern in flamenco is this one:

The two layers are often clapped, but for some reason, my percussion example didn't want to be embedded. As you can see the one player keeps a steady pattern that is in 6/8 while the other plays alternating measures of 6/8 and 3/4. The effect is quite remarkable. We find this kind of pattern in, for example, the bulerias:

This is Sabicas, a real master of the bulerias. He is not actually playing the pattern I have shown above, except in bits, but you will find that you can clap it along with him.

So, that's the hemiola.

So someone who was in love with hemiola would be a "hemiolaphiliac". Or something.

Hermiola is a very interesting rhythmic effect that comes from changing the grouping of beats. We first start seeing it in Spanish music in the 16th century. It usually occurs in triple time as follows. This is from a Baxa de contrapunto by Luys de Narvaez published in 1538:

The hemiola occurs in the third and fourth measures when tieing the A over the barline turns two measures of 3/4 into one measure of 3/2. This became a popular way of signalling a cadence in the Baroque. But the hemiola became quite ubiquitous in Spanish music. A famous example is this Canarios by Gaspar Sanz from the 17th century:

Instead of just appearing at the end or a cadence, this alternation between two groups of three beats and three groups of two beats, shown in the example by the changing time signature from 6/8 to 3/4, happens throughout the piece. We find this a typical rhythmic effect in Spanish music. It appears at the beginning of the famous Concierto de Aranjuez for guitar and orchestra by Joaquin Rodrigo:

There are a couple of nice things about this deceptively simple opening. First of all, it is a three-measure phrase, which is unusual. It has an urgency about it that comes from squeezing the last two measures of a theoretical four-measure phrase into one. The first two measures are a typical hemiola. The third measure is a compressed version of the same hemiola! Let's listen to that opening:

Very nice. Do you hear how that third measure throws us forward? The unusual rhythmic patterns of flamenco underlie a lot of Spanish music. The history of flamenco is somewhat obscure, but undoubtedly some of its unusual handling of rhythm and timbre, by European standards, comes from the long occupation of Spain--some 700 years--by the Moors. One hemiola-related pattern in flamenco is this one:

The two layers are often clapped, but for some reason, my percussion example didn't want to be embedded. As you can see the one player keeps a steady pattern that is in 6/8 while the other plays alternating measures of 6/8 and 3/4. The effect is quite remarkable. We find this kind of pattern in, for example, the bulerias:

This is Sabicas, a real master of the bulerias. He is not actually playing the pattern I have shown above, except in bits, but you will find that you can clap it along with him.

So, that's the hemiola.

:.

:.